Comedy Performers

One of my least favourite TV formats is the tribute to a comedy legend – Tommy Cooper, say, or Billy Connolly or Les Dawson – where they show a load of the subjects’ best bits interspersed with clips of modern C-list celebrities explaining to someone off camera why they’re so funny. Here’s a better idea: just show more of the legend and cut out the C-list celebrities. It’ll be cheaper – and funnier.

So I’m not going to explain why these people are funny, you either get them or you don’t, I just want to acknowledge their genius and maybe recall the first time I realised they were good. Some of them go back a long way, but something about them stuck, and I want to pay tribute to that. Quality doesn’t age.

Rowan Atkinson

(1955–)

After Eights; Blackadder; Mr. Bean

Richard Curtis tells the story of how at the end of a revue writers’ meeting once (early 1976, it would have been, at University College, Oxford, in the rooms of chemistry don John Albery) a quiet, dark-haired figure, after sitting virtually silent through most of our deliberations, at last rose elegantly from the sofa and performed a little wordless sketch where all he did was offer a letter to various members of his audience using a minimum of throaty vocalisations and an extraordinary range of facial expressions. For five minutes. Which is slightly less than how long we laughed for. And look what he’s done since. You had to be there. And I’m happy to say I was, where it all began. (Asked about this a few years ago on Stephen Colbert’s US chat show, Rowan gave a small demonstration of that extraordinary performance with his customary humility and grace. Do seek it out.)

Ronnie Barker

(1929–2005)

The Two Ronnies; Porridge

Sir Peter Hall regretted never having been able to direct Ronnie Barker as Falstaff. But the man was so versatile he could have played Lear with equal facility and conviction. Or, given his propensity for drag, probably Cleopatra as well. His Two Ronnies scripts, delivered under the pen name Gerald Wiley, were so verbally dextrous that before he was outed, people thought they were actually by Tom Stoppard. Of course, Ronnie B had been in the original production of Stoppard’s The Real Inspector Hound opposite Richard Briers in 1968, so maybe that’s where the rumours started. Also to be thanked for putting me on to Jo Stafford’s masterful rendition of that lush fifties standard, ‘You Belong To Me’, where the singer’s timbre is matched only by the timing of Mr Barker himself in the episode ‘A Night In’. Note that Fletch warbles “See duh pyramids acrawss duh Nyawl” while the lovely Jo Stafford sings the correct lyric, “See the pyramids along the Nile.” I have no idea whether the alteration was deliberate or not, Barker’s or Fletch’s, though I fancy the latter – because he could make it sound funnier that way while still making his point.

Richard Beckinsale

(1947–1979)

Porridge; Rising Damp

While Jack Rosenthal’s The Lovers, an early success, may have been a bit twee for my taste, it was Rising Damp and the peerless Porridge which really proved Richard Beckinsale’s worth. Those laid-back, charming, sparkly performances will be his monument, no less than his lovely and talented actress daughters Samantha and Kate. The accent didn’t hurt either. Richard B’s Midlands vowels were part of the wave that helped sweep away all the RP barriers that had constrained the medium for so long, building on the likes of Clement and La Frenais’s own Likely Lads and laying the foundations for their Geordie brickies in Auf Wiedersehen, Pet et al.

Beyond the Fringe

(1960)

Individually and collectively, this foursome was about as intellectually formidable as any cast every assembled. They wrote it all themselves at a time when verbal skills were still the root of stage comedy, with less reliance on silly voices or lazy catchphrases. And they performed it in a deadpan, unflashy style that highlighted rather than distracted from the unprecedented scurrilousness of the content. As one of them remarked, they didn’t invent satire – people had been debunking the so-called great and good behind closed doors forever – it’s just that here they were finally making that kind of private dissatisfaction public. All this and Dudley Moore’s fabulous piano-playing. They – and we – were truly blessed. No women, of course, but you can’t have everything at once, and luckily the likes of Millicent Martin and Eleanor Bron were already warming up in the wings.

Patrick Cargill

(1918–1996)

The Blood Donor; Father, Dear Father

He was the caustic doctor in the first, opposite Tony Hancock (“We’re not all Rob Roys”), and the harassed father of two nubile daughters in the second, a TV sitcom which was cosy and middle class af, but I envied that rich writer’s lifestyle and his big Saint Bernard, HG Wells. I think I even saw him on the Tube once, it must have been in the late seventies. He was sitting quietly in the corner in a big beige overcoat, like a retired army general, with a neatly rolled umbrella, looking dignified and dependable. And alone. I hope he was happy because, for all the enjoyment he had given me and so many others, he deserved to be.

Paul Eddington

(1927–1995)

The Good Life; Yes, Minister

He played Will Scarlett in The Adventures of Robin Hood in the late fifties and then various heavies and spies and captains of industry throughout the sixties, but it was The Good Life that finally brought him the recognition that he always had coming. A gentle soul, a good man, you liked him and wanted to be on his side. On screen he gave the impression he was always trying to do his best, often in the face of self-doubt and in the teeth of opposition from others, sometimes even those closest to him (looking at you Margo, you were never that nice). His scenes of mild grown-up flirtation with the incomparable Felicity Kendal as Barbara are masterpieces of gentle, human comedy, terribly sweet and perfectly judged.

Joyce Grenfell

(1910–1979)

Everyone knows “George, don’t do that” but she also said things like “I posted that rabbit” and did the best solo sketch about an old girls’ school reunion you’re ever likely to see. (Her character’s surname is Clinch, but on meeting her old French teacher she pronounces it the French way, Clahnshe. Because of course she does.) She was posh and funny decades before Miranda Hart and Phoebe Waller-Bridge, but her extra dimension of dignity is something I particularly miss. No falling over her own feet or calling herself Fleabag. And she could sing too. And remember those glorious old-school quality programmes from BBC2 in the early seventies, like Face the Music, which she so frequently graced? They simply don’t make stuff like that anymore, because not enough people seem capable of appreciating that level of all-round talent. Shame. Damn shame.

Tony Hancock

(1924–1968)

The Blood Donor et al

In the end, he turned out to be his own worst enemy by constantly urging on his most faithful acolytes to greater efforts while being seemingly unable to lead them to new heights himself. He let go stalwart supports, the likes of Sid James and Kenneth Williams, apparently fearful their skills might overshadow his own, without realising that far from being a threat, they were, along with Galton and Simpson’s scripts, among his greatest assets. But once he’d sloughed them off too, there was no avoiding the death spiral. Could The Blood Donor have been any funnier if he hadn’t been reading half of it off cue cards? He was so good, it hardly mattered. The tragedy was, once he’d discovered he could do it and get away with it – the result of some car accident which had made it difficult for him to learn that week’s script properly – he rarely bothered to do it any other way again, hampering the endless possibilities in that dour, lugubrious face.

Frankie Howerd

(1917–1992)

Up Pompeii!

Our astute Latin master in school advised us, his class of hormonal dullards, to watch the 1969 sitcom Up Pompeii! on TV. Of course, it didn’t help our Latin much, but the girls fuelled our fantasies and made us more attentive to any other such pearls he might care to drop at our porcine trotters. Frankie Howerd, reviving his Pseudolus persona from the Stephen Sondheim musical A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, rightly scored one of the biggest hits of his storied career both in the series and the 1971 spin-off film. Fifty-plus years on, both series and film now appear unwatchably naff, but Howerd’s ability to wrestle the audience over to his side in the teeth of threadbare material remains unrivalled and still admirable.

Sir David Jason

(1940–)

Do Not Adjust Your Set; The Top Secret Life of Edgar Briggs

Way before the biggies like Only Fools and Horses and Open All Hours, some of us were already aware of the little man’s brilliance through his frequent appearances with half the Pythons and the other half of the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band in Do Not Adjust Your Set, and then the spy spoof The Top Secret Life of Edgar Briggs. He didn’t even need to be in The Darling Buds of May after all that. There is an urban legend to the effect that Elton John was such a fan of DJ’s Captain Fantastic character from DNAYS that he named a whole album after him. I’m glad he didn’t make a habit of that. ‘Your Song’ might lose some of its plangency if we knew it had first appeared on the album Del Boy.

Hugh Laurie

(1959–)

Blackadder; Jeeves and Wooster; Sense and Sensibility

I was never a great fan of his George IV – always thought the characterisation a bit broad and lacking in subtlety – but his Bertie Wooster was as definitive as Jeremy Brett’s Sherlock Holmes or Joan Hickson’s Miss Marple, and his Mr. Palmer in Sense and Sensibility, written by his old Cambridge University squeeze Emma Thompson, was both quietly hilarious and ultimately touching. The way he silently straightens the corner of the newspaper that his over-enthusiastic wife, Imelda Staunton, had scrunched – grace under pressure. There’s a man we can all learn from…

Monty Python

(1969)

Monty Python’s Flying Circus; Life of Brian; The Meaning of Life

Ten years after the satire of Beyond the Fringe we got the zany of Monty Python. My generation were hooked. Just as your favourite music is always the stuff you listened to in your teens, so many of my generation will hold up the Pythons as the comedy group to beat… just as our parents will point at The Goon Show and say “Wait a minute,” or our younger cousins might protest “What about Not the Nine O’Clock News?” and their offspring The Fast Show, and so on. I’m just glad they did what they did, then. Not so sure their brand of humour would still hack it today, but maybe that’s because, as pioneers, they wrote the rule book then ripped it up. And why is the ‘Dead Parrot Sketch’ frequently cried up as the GOAT? Because they did that as one of the encores on their Live at the Hollywood Bowl album. After howling with mirth for two hours, the audience were so hyped up they would have given a standing ovation to a reading of the telephone directory. Or even one of their weaker sketches. Timing is, in comedy, after all, all, innit?

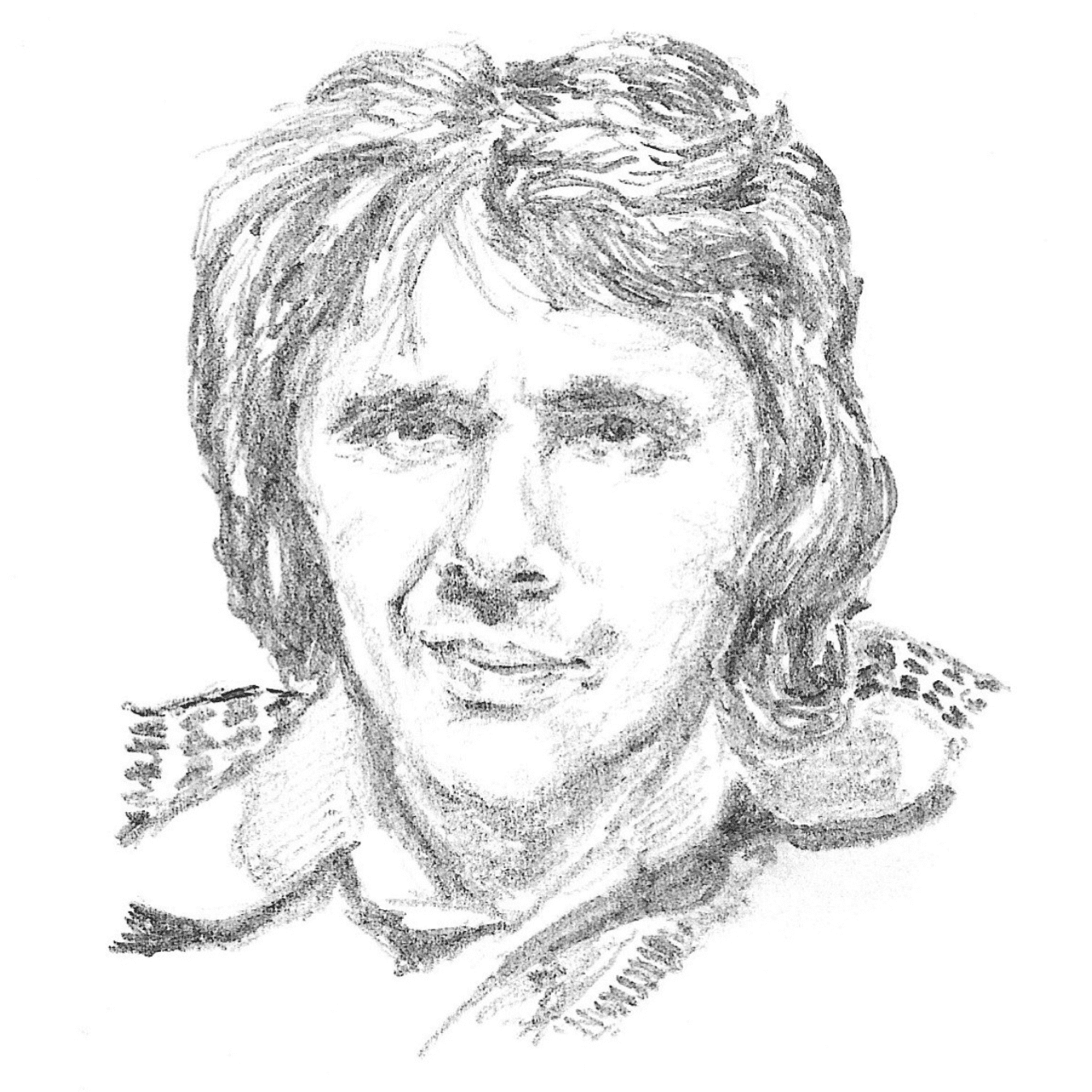

Richard O’Sullivan

(1944–)

Man About the House; Robin’s Nest

He’d been in films for ten years even before he appeared opposite Elizabeth Taylor as her brother Ptolemy XIII in the notorious epic Cleopatra (1963), so it’s hardly surprising that by the time these two inoffensively forgettable sitcoms came along, he had a wealth of experience to draw on. Just glancing down his IMDb page, you can see they couldn’t have chosen better when they were casting Herbert Pocket in the 1967 TV Great Expectations, or the jaunty highwayman Dick Turpin in the late seventies. It was his super-relaxed delivery I liked, never over-emphasising, and that inborn disarming smirk.

Miranda Richardson

(1958–)

Blackadder

There’s something a bit mad about her, isn’t there, and her secret power is you’re never sure if it’s her or the part. Certainly she got the role of Queenie by auditioning with the most off-the-wall and unexpected reading that anyone had given. But the best comedy performers are invariably the best actors anyway, and she had already been so good as the tragic Ruth Ellis in Dance With a Stranger (1985) that she spent the next few years having to fend off parts that just wanted to see that characterisation again, the unstable beauty you couldn’t turn your back on for a minute (the Glenn Close part in Fatal Attraction, for instance). Which is precisely what makes her comic Queen Elizabeth so riveting. She’s scary as hell. But also undeniably, and awfully, sexy, dammit.

Leonard Rossiter

(1926–1984)

Rising Damp; Cinzano ads

His character in each was as deft and fully rounded as the other, but while Rigsby was a broad caricature, to be able to make your mark in a series of a dozen or so drinks ads on the telly, each barely thirty seconds long, takes class. The peerless Joan Collins was equally indispensable, of course, but the oaf was the focus. Then again, he had always been good; Kubrick put him in 2001 in 1968, then had him back again for Barry Lyndon in 1975. But in between he played an escaped convict in The Desperate Hours, one of the most brilliant Steptoe and Sons. At one point, hoping to make a quick few quid, he orders Harold to empty his pockets. Harold sheepishly unloads his entire wealth – it comes to maybe 3½p. The look that passes between them is funny, profound, and heart-breaking. And brilliantly observed.

Dame Patricia Routledge

(1929–2025)

Kitty (Victoria Wood: As Seen on TV); Talking Heads

Another peerless British performer with years of experience that was finally recognised and rewarded through sitcoms and drama appearances alike. I never took to Hyacinth Bouquet for the same reason I never liked Margo Leadbetter – they are bullies who are allowed to get away with it – but the monologues Victoria Wood supplied for her as Kitty are superbly crafted and object lessons in character comedy. Lancashire lass Wood shared a lot of observational comic DNA with Yorkshireman Alan Bennett, and Patricia R also scored a palpable hit in two of Bennett’s Talking Heads monologues: A Woman of No Importance and A Lady of Letters. One starts off laughing at them, and ends up crying with them. It’s a trick very few writers can pull off, but you need a performer of this calibre to have a chance for it to work at all.

Dame Emma Thompson

(1959–)

Thompson

In order to write and star in your own self-named TV sketch show before you’re thirty you must be doing something right. And this was before the Oscar-winning screenplay for Sense and Sensibility. It’s genes to some extent, of course; when your mother is an actress and your father wrote and voiced the English version of The Magic Roundabout for years, something’s bound to rub off. But to play a grotesque like Nanny McPhee one day and move audiences around the world with a single crying scene in Love Actually the next, that takes talent of the next level. Someone once referred to Emma T’s “lack of conventional beauty” contributing to her likeability as an actress. Lack of what now? You should be so lucky, missus.

Richard Wilson

(1936–)

Only When I Laugh; British Telecom TV commercials; One Foot in the Grave

If they ever make a biopic of Alastair Sim, Richard Wilson would be the man to play him. Or he would have been; he might be getting a bit too long in the tooth now, but in his day, he was as deft a light comedian as his distinguished predecessor. By the time he came to do those BT commercials opposite Maureen Lipman in the early nineties, he had already established himself through daytime stalwart Crown Court and the Eric Chappell sitcom Only When I Laugh. But once again it was the commercials that proved the point. You have to know your stuff. We were already on his side by the time the world started pooping in Victor Meldrew’s hat in One Foot in the Grave.

Dame Julie Walters

(1950–)

Victoria Wood shows

She was lucky to find Victoria Wood, certainly, but that cut both ways, and that’s even before you contemplate the friendship they enjoyed quite independently of their professional onscreen chemistry. I have a particular fondness for women who don’t stand on their dignity all the time, who are prepared to do whatever it takes to get the laugh, and if that means sitting in a sauna with your bra on the outside, or staggering through the Acorn Antiques set in wrinkled tights and a Marigold glove hanging out the front pocket of your pinny like a flaccid udder, then let’s do lunch. Not to mention the TV commercial set in a science lab (can’t remember what it was advertising now) wherein with a perfectly straight face the lady delivers the line, “Nothing beats a good boffin.” I’ll admit, it took me a while…

Dame June Whitfield

(1925–2018)

Birds Eye TV commercials et al

Her 2000 autobiography was entitled And June Whitfield and that’s basically, and literally, the story of her life. Since the early fifties, she supported them all – Jimmy Edwards, Arthur Askey, Benny Hill, Frankie Howerd, Tony Hancock, Terry Scott, Jennifer Saunders and countless others. She was pert, pretty, perfect, and always appeared ladylike while looking, at the same time, like a lot of fun. It was probably the twinkly eyes. But it was those commercials for Birds Eye I remember, and the wide range of characters she played. My favourite was the regal queen (“The Basrovian ambassador’s coming to tea and the chef’s gorn orff, so I’ve sent ite for some Birds Eye chicken pie.”). Later the Basrovian ambassador asks her if she made it herself. “Ishney da,” she lies, in perfect Basrovian with that inimitable cut-glass accent, and suffers the accusatory glare of an eavesdropping footman. If only all comedy commercials were still this good. But you can’t get the performers. (Dominic West in that one for the building society maybe. But what’s the name of the building society? See what I mean?)

Victoria Wood

(1953‒2016)

That’s Life; Wood and Walters; dinnerladies

One of the dinnerladies talks about somebody having an accident and scratching her Volvo. Another one asks “Can you smell my Charlie?”, it having been carefully established beforehand that this is a brand of perfume. Someone else causes confusion by mixing up the word Urdu and the northern pronunciation of the word ‘hairdo’. The title of her first stage play, Talent in 1978, says it all: when it came to comedy, there was nothing Victoria Wood couldn’t do better than just about anybody else. Remember that TV sketch about the young Channel swimmer completely ignored by her parents? Greasing herself up on the beach one early morning and plunging into the cold grey sea with a kid’s duffle bag over her shoulder, never to be seen again? She wrote that, knowing she was going to have to do it for real some raw morning off the bloody awful coast of Filey or Sheerness or somewhere. Talk about brave. Talk about heartbreaking. And talk about stamina. At the end of one of her two-hour stage shows she reappeared for her second encore in a leotard and did a ten-minute exercise routine, still talking while doing step aerobics. After a two-hour show! Everything I know about women, I learnt from Victoria Wood. She was clear-eyed, unsentimental, pitch-perfect, and irreplaceable.

Harry Worth

(1917–1989)

Various TV series with his name in the title

There were a few of these old stage pros on TV in the sixties – Charlie Drake, Norman Vaughan, Alfie Bass, Bill Fraser, Ted Ray etc – but I remember Harry Worth for that trick he did with the shop window reflection. I could never work it out. Did they rig it so once he’d positioned himself at the corner, a metal pole slid across between his legs which he sat on like a bicycle saddle so he could then do the thing with his arms and legs? (The answer, of course, is no.) He did innocent bumbling better than anyone, then in the early seventies he was cast as William Boot in an ill-judged TV adaptation of Evelyn Waugh’s Scoop, and it wasn’t his fault he was twenty years too old for the part. But on the other hand, in that version Kätchen was played by Sinéad Cusack, so they could have put Bernard Manning opposite her and I’d still have watched. Comedy is all very well, but beauty like that is everything else.